- Home

- David Downing

Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Read online

Also by David Downing

Zoo Station

Silesian Station

Stettin Station

Potsdam Station

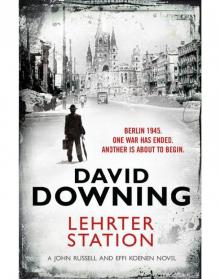

Lehrter Station

Masaryk Station

Copyright © 2014 by David Downing

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Downing, David, 1946–

Jack of spies / David Downing.

p. cm

ISBN 978-1-61695-268-6

eISBN: 978-1-61695-269-3

1. Scots—Fiction. 2. Sales personnel—Fiction. 3.

Selling—Automobiles—Fiction. 4. Espionage, British—Fiction.

5. Man-woman relationships—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6054.O868J33 2014

823′.914—dc23 2013038342

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

v3.1

To Nancy

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Blue Dragon

The House Off Bubbling Well Road

Stateroom 302

The Shamrock Saloon

Compartment 4

The Giant Racer

Mill-Town Alley

Staten Island Ferry

Hotel México

Oakley Street

Killoran’s Tavern

The Arun Bridge

The Blue Dragon

At the foot of the hill, Tsingtau’s Government House stood alone on a slight mound, its gabled upper-floor windows and elegant corner tower looking out across the rest of the town. Substantial German houses with red-tiled roofs peppered the slope leading down to the Pacific beach and pier; beyond them the even grander buildings of the commercial district fronted the bay and its harbors. Away to the right, the native township of Taipautau offered little in the way of variety—the houses were smaller, perhaps a bit closer together, but more European than classically Chinese. In less than two decades, the Germans had come, organized, and recast this tiny piece of Asia in their own image. Give them half a chance, Jack McColl mused, and they would do the same for the rest of the world.

He remembered the Welsh mining engineer leaning over the Moldavia’s rail in mid–Indian Ocean and spoiling a beautiful day with tales of the atrocities the Germans had committed in South-West Africa over the last few years. At least a hundred thousand Africans had perished. Many of the native men had died in battle; most of the remainder, along with the women and children, had been driven into the desert, where some thoughtful German had already poisoned the water holes. A few lucky ones had ended up in concentration camps, where a doctor named Fischer had used them for a series of involuntary medical experiments. Children had been injected with smallpox, typhus, tuberculosis.

The white man’s burden, as conceived in Berlin.

McColl had passed two descending Germans on his way up the hill, but the well-kept viewing area had been empty, and there was no sign of other sightseers below. To the east the hills rose into a jagged horizon, and the earthworks surrounding the 28-centimeter guns on Bismarck Hill were barely visible against the mountains beyond. Some magnification would have helped, but an Englishman training binoculars on foreign defenses was likely to arouse suspicion, and from what he’d seen so far, the guns were where the Admiralty had thought they would be. There was some building work going on near the battery that covered Auguste-Victoria Bay, but not on a scale that seemed significant. He might risk a closer look early one morning, when the army was still drilling.

The East Asia Squadron was where it had been the day before—Scharnhorst and Emden sharing the long jetty, Gneisenau and Nürnberg anchored in the bay beyond. Leipzig had been gone a week now—to the Marianas, if his Chinese informer was correct. Several coalers were lined up farther out, and one was unloading by the onshore wharves, sending occasional clouds of black dust up into the clear, cold air.

These ships were the reason for his brief visit, these ships and what they might do if war broke out. Their presence was no secret, of course—the local British consul probably played golf with the admiral in command. The same consul could have kept the Admiralty informed about Tsingtau’s defenses and done his best to pump his German counterpart for military secrets, but of course he hadn’t. Such work was considered ungentlemanly by the fools who ran the Foreign Office and staffed its embassies—not that long ago a British military attaché had refused to tell his employers in London what he’d witnessed at his host country’s military maneuvers, on the grounds that he’d be breaking a confidence.

It was left to part-time spies to do the dirty work. Over the last few years, McColl—and, he presumed, other British businessmen who traveled the world—had been approached and asked to ferret out those secrets the empire’s enemies wanted kept. The man who employed them on this part-time basis was an old naval officer named Cumming, who worked from an office in Whitehall and answered, at least in theory, to the Admiralty and its political masters.

When it came to Tsingtau, the secret that mattered most was what orders the East Asia Squadron had for the day that a European war broke out. Any hard evidence as to their intentions, as Cumming had told McColl on their farewell stroll down the Embankment, would be “really appreciated.”

His insistence on how vital all this was to the empire’s continued well-being had been somewhat undermined by his allocation of a paltry three hundred pounds for global expenses, but the trip as a whole had been slightly more lucrative than McColl had expected. The luxury Maia automobile that he was hawking around the world—the one now back in Shanghai, he hoped, with his brother Jed and colleague Mac—had caught the fancy of several rulers hungry for initiation into the seductive world of motorized speed, and the resultant orders had at least paid the trio’s traveling bills.

This was gratifying, but probably more of a swan song than a sign of things to come. The automobile business was not what it had been even two years before, not for the small independents—nowadays you needed capital, and lots of it. Spying, on the other hand, seemed an occupation with a promising future. Over the last few years, even the British had realized the need for an espionage service, and once the men holding the purse strings finally got past the shame of it all, they would realize that only a truly professional body would do. One that paid a commensurate salary.

A war would probably help, but until Europe’s governments were stupid enough to start one, McColl would have to make do with piecework. Before McColl’s departure from England the previous autumn, Cumming had taken note of his planned itinerary and returned with a list of “little jobs” that McColl could do in the various ports of call—a wealthy renegade to assess in Cairo, a fellow Brit to investigate in Bombay, the Germans here in Tsingtau. Their next stop with the Maia was San Francisco, where a ragtag bunch of Indian exiles were apparently planning the empire’s demise.

A lot of it seemed pretty inconsequential to McColl. There were no doubt plenty of would-be picadors intent on goading the imperial bull, but it didn’t seem noticeably weaker. And where was the matador to finish it off? The Kaiser probably practiced sword strokes in his bedroom mirror, but it would be a long time before Germany acquired the necessary global reach.

He lit a German cigarette and stared out across the town. The sun was dropping toward the distant horizon, the harbor lighthouse glowing brighter by the minute. The lines of lamps in the warship rigging reminded him of Christmas trees.

He would be back in Shanghai for the Chinese New Year, he realize

d.

Caitlin Hanley, the young American woman he’d met in Peking, was probably there already.

The sun was an orange orb, almost touching the distant hills. He ground out the cigarette and started back down the uneven path while he could still see his way. Two hopeful coolies were waiting with their rickshaws at the bottom, but he waved them both away and walked briskly down Bismarckstrasse toward the beach. There were lights burning in the British consulate, but no other sign of life within.

His hotel was at the western end of the waterfront, beyond the deserted pleasure pier. The desk clerk still had his hair in a pigtail—an increasingly rare sight in Shanghai but common enough in Tsingtau, where German rule offered little encouragement to China’s zealous modernizers. The room key changed hands with the usual bow and blank expression, and McColl climbed the stairs to his second-floor room overlooking the ocean.

A quick check revealed that someone had been though his possessions, which was only to be expected—Tsingtau might be a popular summer destination with all sorts of foreigners, but an Englishman turning up in January was bound to provoke some suspicion. Whoever it was had found nothing to undermine his oft-repeated story, that he was here in China on business and seeing as much of the country as money and time would allow.

He went back downstairs to the restaurant. Most of the clientele were German businessmen in stiff collars and spats, either eager to grab their slice of China or boasting of claims already staked. There were also a handful of officers, including one in a uniform McColl didn’t recognize. He was enthusiastically outlining plans for establishing an aviation unit in Tsingtau when he noticed McColl’s arrival and abruptly stopped to ask the man beside him something.

“Don’t worry, Pluschow, he doesn’t speak German,” was the audible answer, which allowed the exposition to continue.

Since his arrival in Tsingtau, McColl had taken pains to stress his sad lack of linguistic skills, and this was not the first time the lie had worked to his advantage. Apparently absorbed in his month-old Times, he listened with interest to the aviation enthusiast. He couldn’t see much strategic relevance in the news—what could a few German planes hope to achieve so far from home?—but the Japanese might well be interested. And any little nugget of intelligence should be worth a few of Cumming’s precious pounds.

The conversation took a less interesting tack, and eventually the party broke up. McColl sipped his Russian tea and idly wondered where he would dine later that evening. He glanced through the paper for the umpteenth time and reminded himself that he needed fresh reading for the Pacific crossing. There was a small shop he knew on Shanghai’s Nanking Road where novels jettisoned by foreigners mysteriously ended up.

More people came in—two older Germans in naval uniform, who ignored him, and a stout married couple, who returned his smile of acknowledgment with almost risible Prussian hauteur.

He was getting up to leave when Rainer von Schön appeared. McColl had met the young German soon after arriving in Tsingtau—they were both staying at this hotel—and taken an instant liking to him. The fact that von Schön spoke near-perfect English made conversation easy, and the man himself was likable and intelligent. A water engineer by trade, he had admitted to a bout of homesickness and delved into his wallet for an explanatory photo of his pretty wife and daughter.

That evening he had an English edition of William Le Queux’s Invasion of 1910 under his arm.

“What do you think of it?” McColl asked him once the waiter had taken the German’s order.

“Well, several things. It’s so badly written, for one. The plot’s ridiculous, and the tone is hysterical.”

“But otherwise you like it?”

Von Schön smiled. “It is strangely entertaining. And the fact that so many English people bought it makes it fascinating to a German. And a little scary, I have to say.”

“Don’t you have any ranters in Germany?”

Von Schön leaned slightly forward, a mischievous expression on his face. “With the Kaiser at the helm, we don’t need them.”

McColl laughed. “So what have you been doing today?”

“Finishing up, actually. I’ll be leaving in a couple of days.”

“Homeward bound?”

“Eventually. I have work in Tokyo first. But after that …”

“Well, if I don’t see you before you go, have a safe journey.”

“You, too.” Von Schön drained the last of his schnapps and got to his feet. “And now I have someone I need to see.”

Once the German was gone, McColl consulted his watch. It was time he visited the Blue Dragon, before the evening rush began. He left a generous tip, recovered his winter coat from the downstairs cloakroom, and walked out to the waiting line of rickshaws. The temperature had already dropped appreciably, and he was hugging himself as the coolie turned left onto the well-lit Friedrichstrasse and started up the hill. The shops were closed by this time, the restaurants readying themselves for their evening trade. The architecture, the faces, the cooking smells, all were European—apart from his coolie, the only Chinese person in sight was a man collecting horse dung.

It was quiet, too—so quiet that the sudden blast of a locomotive whistle from the nearby railway station made him jump.

The coolie reached the brow of the low hill and started down the opposite slope into Taipautau. The township was almost as neat and widely spaced as the German districts, and in the cold air even the smells seemed more muted than they had in Shanghai. They were halfway down Shantung Strasse before McColl could hear the beginnings of evening revelry in the sailors’ bars at the bottom.

The Blue Dragon was open for business but not yet really awake. The usual old man sat beneath the candlelit lanterns on the rickety veranda, beside the screened-off entrance. He grinned when he recognized McColl and cheerfully spat on the floor to his right, adding one more glistening glob to an impressive mosaic.

McColl was barely through the doorway when an old woman hurried down the hall toward him. “This way, please!” she insisted in pidgin German. “All type girls!”

“I’m here to see Hsu Ch’ing-lan,” he told her in Mandarin, but she just looked blank. “Hsu Ch’ing-lan,” he repeated.

The name seemed to percolate. She gestured for him to follow and led him through to the reception area, where “all type girls” were waiting in an assortment of tawdry traditional costumes on long red-velvet sofas. Some were barely out of puberty, others close to menopause. One seemed amazingly large for a Chinese woman, causing McColl to wonder whether she’d been fattened up to satisfy some particular Prussian yearning.

The old woman led him down the corridor beyond, put her head around the final door, and told Madame that a laowai wanted to see her. Assent forthcoming, she ushered McColl inside.

Hsu Ch’ing-lan was sitting at her desk, apparently doing her accounts. Some kind of incense was burning in a large dragon holder beyond, sending up coils of smoke.

“Herr McColl,” she said with an ironic smile. “Please. Take a seat.”

She was wearing the usual dress, blue silk embroidered in silver and gold, ankle-length but slit to the hip. Her hair was piled up in curls, secured by what looked like an ornamental chopstick. She was in her thirties, he guessed, and much more desirable than any of the girls in reception. When they’d first met, she’d told him that she was a retired prostitute, as if that were a major achievement. It probably was.

He had chosen this brothel for two reasons. It offered a two-tier service—those girls in reception who catered to ordinary sailors and the occasional NCO, and another, more exclusive, group who did house calls at officers’ clubs and businessmen’s hotels. The latter were no younger, no more beautiful, and no more sexually inventive than the former, but as Jane Austen might have put it, they offered more in the way of accomplishments. They sang, they danced, they made a ritual out of making tea. They provided, in Ch’ing-lan’s vivid phrase, “local-color fuck.”

She was hi

s second reason for choosing the place. She came from Shanghai and, unlike any other madam in Tsingtau, spoke the Chinese dialect that McColl knew best.

She pulled a bell cord, ordered tea from the small girl who came running, and asked him, rather surprisingly, what he knew of the latest political developments.

“In China?” he asked.

She looked at him as if he were mad. “What could matter here?” she asked.

“Sun Yat-sen could win and start modernizing the country,” he suggested. “Or Yuan Shih-kai could become the new emperor and keep the country locked in the past.”

“Pah. You foreign devils have decided we must modernize, so Yuan cannot win. And you control our trade, so Sun could win only as your puppet.”

“Yuan bought one of my cars.”

“He thinks it will make him look modern, but it won’t. It doesn’t matter what he or Sun does. In today’s China everything depends on what the foreign devils do. Is there going to be a war between you? And if there is, what will happen here in Tsingtau?”

“If there’s a war, the Japanese will take over. The Germans might dig themselves in—who knows? If they do, the town will be shelled. If I were you, I’d take the boat back home to Shanghai before the fighting starts.”

“Mmm.” Her eyes wandered around the room, as if she were deciding what to take with her.

The tea arrived and was poured.

“So what do you have for me?” McColl asked.

“Not very much, I’m afraid.” The East Asia Squadron was going to sea at the end of February, for a six-week cruise. The Scharnhorst had a new vice captain, and there’d been a serious accident on the Emden—several sailors had been killed in an explosion. The recent gunnery trials had been won by the Gneisenau, but all five ships had shown a marked improvement, and the Kaiser had sent a congratulatory telegram to Vice Admiral von Spee. And a new officer had arrived from Germany to set up a unit of flying machines.

“I know about him,” McColl said.

“He likes to be spanked,” Ch’ing-lan revealed.

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave The Dark Clouds Shining

The Dark Clouds Shining Masaryk Station (John Russell)

Masaryk Station (John Russell) Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Zoo Station jr-1

Zoo Station jr-1 Masaryk Station

Masaryk Station One Man's Flag

One Man's Flag Potsdam Station jr-4

Potsdam Station jr-4 Stattin Station jr-3

Stattin Station jr-3 Masaryk Station jr-6

Masaryk Station jr-6 Silesian Station (2008) jr-2

Silesian Station (2008) jr-2 Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Silesian Station (2008)

Silesian Station (2008) The Moscow Option

The Moscow Option The Red Eagles

The Red Eagles Zoo Station

Zoo Station Lehrter Station

Lehrter Station Lehrter Station jr-5

Lehrter Station jr-5