- Home

- David Downing

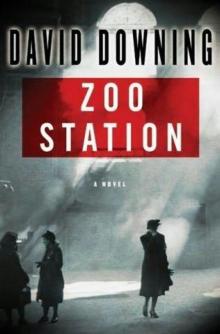

Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Read online

Table of Contents

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

AUTHORS NOTE

Into the Blue

Ha! Ho! He!

The Knauer Boy

Zygmunts Chapel

Idiots to Spare

Achievements of the Third Reich

Blue Scarf

Left Luggage

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

The Moscow Option

Russian Revolution 1985

The Red Eagles

Copyright Š 2007 by David Downing

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Downing, David, 1946-

Zoo Station: a novel / David Downing. p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56947-454-9 (hardcover)

eISBN : 97-8-156-94779-1

1. AmericansGermanyBerlinFiction. 2. JournalistsGermanyBerlinFiction. 3. GermanyHistory1933-1945Fiction. 4. SpiesRecruitingFiction. I. Title.

PR6054.O868Z66 2007

823.914dc22

2006026918

1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

in memory of

Martha Pappenheim (1900-2001)

who escaped from Germany in 1939

and went on to help the children

of those who did not

and

Yvonne Pappenheim (1912-2005)

who married Marthas brother Fritz

and spent a lifetime fighting injustice

AUTHORS NOTE

This is a work of fiction, but every attempt has been made to keep within the bounds of historical possibility. References to the Nazis planned murder of the mentally handicapped are mostly drawn from Michael Burleighs exhaustive history Death and Deliverance, and even the more ludicrous of the news stories mentioned in passing are depressingly authentic.

Into the Blue

THERE WERE TWO HOURS left of 1938. In Danzig it had been snowing on and off all day, and a gang of children was enjoying a snowball fight in front of the grain warehouses which lined the old waterfront. John Russell paused to watch them for a few moments, then walked on up the cobbled street toward the blue and yellow lights.

The Sweden Bar was far from crowded, and those few faces that turned his way werent exactly brimming over with festive spirit. In fact, most of them looked like theyd rather be somewhere else.

It was an easy thing to want. The Christmas decorations hadnt been removed, just allowed to drop, and they now formed part of the flooring, along with patches of melting slush, floating cigarette butts, and the odd broken bottle. The bar was famous for the savagery of its international brawls, but on this particular night the various groups of Swedes, Finns, and Letts seemed devoid of the energy needed to get one started. Usually a table or two of German naval ratings could be relied upon to provide the necessary spark, but the only Germans present were a couple of aging prostitutes, and they were getting ready to leave.

Russell took a stool at the bar, bought himself a Goldwasser, and glanced through the month-old copy of the New York Herald Tribune which, for some inexplicable reason, was lying there. One of his own articles was in it, a piece on German attitudes to their pets. It was accompanied by a cute-looking photograph of a Schnauzer.

Seeing him reading, a solitary Swede two stools down asked him, in perfect English, if he spoke that language. Russell admitted that he did.

You are English! the Swede exclaimed, and shifted his considerable bulk to the stool adjoining Russells.

Their conversation went from friendly to sentimental, and sentimental to maudlin, at what seemed like a breakneck pace. Three Goldwassers later, the Swede was telling him that he, Lars, was not the true father of his children. Vibeke had never admitted it, but he knew it to be true.

Russell gave him an encouraging pat on the shoulder, and Lars sunk forward, his head making a dull clunk as it hit the polished surface of the bar. Happy New Year, Russell murmured. He shifted the Swedes head slightly to ease the mans breathing, and got up to leave.

Outside, the sky was beginning to clear, the air almost cold enough to sober him up. An organ was playing in the Protestant Seamens Church, nothing hymnal, just a slow lament, as if the organist were saying a personal farewell to the year gone by. It was a quarter to midnight.

Russell walked back across the city, conscious of the moisture seeping in through the holes in his shoes. There were lots of couples on Langer Markt, laughing and squealing as they clutched each other for balance on the slippery sidewalks.

He cut over to Breite Gasse and reached the Holz-Markt just as the bells began pealing in the New Year. The square was full of celebrating people, and an insistent hand pulled him into a circle of revelers dancing and singing in the snow. When the song ended and the circle broke up, the Polish girl on his left reached up and brushed her lips against his, eyes shining with happiness. It was, he thought, a better-than-expected opening to 1939.

HIS HOTELS RECEPTION AREA was deserted, and the sounds of celebration emanating from the kitchen at the back suggested the night staff were enjoying their own private party. Russell gave up the idea of making himself a hot chocolate while his shoes dried in one of the ovens, and took his key. He clambered up the stairs to the third floor, and trundled down the corridor to his room. Closing the door behind him, he became painfully aware that the occupants of the neighboring rooms were still welcoming in the new year, loud singing on one side, floor-shaking sex on the other. He took off his shoes and socks, dried his wet feet with a towel, and sank back onto the vibrating bed.

There was a discreet, barely audible tap on his door.

Cursing, he levered himself off the bed and pulled the door open. A man in a crumpled suit and open shirt stared back at him.

Mr. John Russell, the man said in English, as if he were introducing Russell to himself. The Russian accent was slight, but unmistakable. Could I talk with you for a few minutes?

Its a bit late . . . Russell began. The mans face was vaguely familiar. But why not? he continued, as the singers next door reached for a new and louder chorus. A journalist should never turn down a conversation, he murmured, mostly to himself, as he let the man in. Take the chair, he suggested.

His visitor sat back and crossed one leg over the other, hitching up his trouser as he did so. We have met before, he said. A long time ago. My name is Shchepkin. Yevgeny Grigorovich Shchepkin. We. . . .

Yes, Russell interrupted, as the memory clicked into place. The discussion group on journalism at the Fifth Congress. The summer of twenty-four.

Shchepkin nodded his acknowledgment. I remember your contributions, he said. Full of passion, he added, his eyes circling the room and resting, for a few seconds, on his hosts dilapidated shoes.

Russell perched himself on the edge of the bed. As you saida long time ago. He and Ilse had met at that conference and set in motion their ten year cycle of marriage, parenthood, separation, and divorce. Shchepkins hair had been black and wavy in 1924; now it was a close-cropped gray. They were both a little older than the century, Russell guessed, and Shchepkin was wearing pretty well, considering what hed probably been through the last fifteen years. He had a handsome face of indeterminate nationality, with deep brown eyes above prominent slanting cheekbones, an aquiline nose, and lips just the full side of perfect. He could have passed for a citizen of most European countries, and probably had.

The Russian completed his survey of the room. This is a dreadful hotel, he said.

/>

Russell laughed. Is that what you wanted to talk about?

No. Of course not.

So what are you here for?

Ah. Shchepkin hitched his trouser again. I am here to offer you work.

Russell raised an eyebrow. You? Who exactly do you represent?

The Russian shrugged. My country. The Writers Union. It doesnt matter. You will be working for us. You know who we are.

No, Russell said. I mean, no Im not interested. I

Dont be so hasty, Shchepkin said. Hear me out. We arent asking you to do anything which your German hosts could object to. The Russian allowed himself a smile. Let me tell you exactly what we have in mind. We want a series of articles about positive aspects of the Nazi regime. He paused for a few seconds, waiting in vain for Russell to demand an explanation. You are not German but you live in Berlin, Shchepkin went on. You once had a reputation as a journalist of the left, and though that reputation hasshall we sayfaded, no one could accuse you of being an apologist for the Nazis . . .

But you want me to be just that.

No, no. We want positive aspects, not a positive picture overall. That would not be believable.

Russell was curious in spite of himself. Or because of the Goldwassers. Do you just need my name on these articles? he asked. Or do you want me to write them as well?

Oh, we want you to write them. We like your styleall that irony.

Russell shook his head: Stalin and irony didnt seem like much of a match.

Shchepkin misread the gesture. Look, he said, let me put all my cards on the table.

Russell grinned.

Shchepkin offered a wry smile in return. Well, most of them anyway. Look, we are aware of your situation. You have a German son and a German lady-friend, and you want to stay in Germany if you possibly can. Of course if a war breaks out you will have to leave, or else they will intern you. But until that moment comesand maybe it wontmiracles do happenuntil it does you want to earn your living as a journalist without upsetting your hosts. What better way than this? You write nice things about the Nazisnot too nice, of course; it has to be crediblebut you stress their good side.

Does shit have a good side? Russell wondered out loud.

Come, come, Shchepkin insisted, you know better than that. Unemployment eliminated, a renewed sense of community, healthy children, cruises for workers, cars for the people. . . .

You should work for Joe Goebbels.

Shchepkin gave him a mock-reproachful look.

Okay, Russell said, I take your point. Let me ask you a question. Theres only one reason youd want that sort of article: Youre softening up your own people for some sort of deal with the devil. Right?

Shchepkin flexed his shoulders in an eloquent shrug.

Why?

The Russian grunted. Why deal with the devil? I dont know what the leadership is thinking. But I could make an educated guess and so could you.

Russell could. The western powers are trying to push Hitler east, so Stalin has to push him west? Are we talking about a non-aggression pact, or something more?

Shchepkin looked almost affronted. What more could there be? Any deal with that man can only be temporary. We know what he is.

Russell nodded. It made sense. He closed his eyes, as if it were possible to blank out the approaching calamity. On the other side of the opposite wall, his musical neighbors were intoning one of those Polish river songs which could reduce a statue to tears. Through the wall behind him silence had fallen, but his bed was still quivering like a tuning fork.

Wed also like some information, Shchepkin was saying, almost apologetically. Nothing military, he added quickly, seeing the look on Russells face. No armament statistics or those naval plans that Sherlock Holmes is always being asked to recover. Nothing of that sort. We just want a better idea of what ordinary Germans are thinking. How they are taking the changes in working conditions, how they are likely to react if war comesthat sort of thing. We dont want any secrets, just your opinions. And nothing on paper. You can deliver them in person, on a monthly basis.

Russell looked skeptical.

Shchepkin ploughed on. You will be well paidvery well. In any currency, any bank, any country, that you choose. You can move into a better apartment block. . . .

I like my apartment block.

You can buy things for your son, your girlfriend. You can have your shoes mended.

I dont. . . .

The money is only an extra. You were with us once. . . .

A long long time ago.

Yes, I know. But you cared about your fellow human beings. I heard you talk. That doesnt change. And if we go under there will be nothing left.

A cynic might say theres not much to choose between you.

The cynic would be wrong, Shchepkin replied, exasperated and perhaps a little angry. We have spilled blood, yes. But reluctantly, and in hope of a better future. They enjoy it. Their idea of progress is a European slave-state.

I know.

One more thing. If money and politics dont persuade you, think of this. We will be grateful, and we have influence almost everywhere. And a man like you, in a situation like yours, is going to need influential friends.

No doubt about that.

Shchepkin was on his feet. Think about it, Mr. Russell, he said, drawing an envelope from the inside pocket of his jacket and placing it on the nightstand. All the details are in herehow many words, delivery dates, fees, and so on. If you decide to do the articles, write to our press attaché in Berlin, telling him who you are, and that youve had the idea for them yourself. He will ask you to send him one in the post. The Gestapo will read it, and pass it on. You will then receive your first fee and suggestions for future stories. The last-but-one letters of the opening sentence will spell out the name of a city outside Germany which you can reach fairly easily. Prague, perhaps, or Cracow. You will spend the last weekend of the month in that city, and be sure to make your hotel reservation at least a week in advance. Once you are there, someone will contact you.

Ill think about it, Russell said, mostly to avoid further argument. He wanted to spend his weekends with Paul, and with Effi, his girlfriend, not the Shchepkins of this world.

The Russian nodded and let himself out. As if on cue, the Polish choir lapsed into silence.

RUSSELL WAS WOKEN BY the scream of a locomotive whistle. Or at least, that was his first impression. Lying there awake all he could hear was a gathering swell of high-pitched voices. It sounded like a school playground full of terrified children.

He threw on some clothes and made his way downstairs. It was still dark, the street deserted, the tramlines hidden beneath a virginal sheet of snow. In the train station booking hall across the street a couple of would-be travelers were hunched in their seats, eyes averted, praying that they hadnt strayed into dangerous territory. Russell strode through the unmanned ticket barrier. There were trucks in the goods yard beyond the far platform, and a train stretched out past the station throat. People were gathered under the yellow lights, mostly families by the look of them, because there were lots of children. And there were men in uniform. Brownshirts.

A sudden shrill whistle from the locomotive produced an eerie echo from the milling crowd, as if all the children had shrieked at once.

Russell took the subway steps two at a time, half-expecting to find that the tunnel had been blocked off. It hadnt. On the far side, he emerged into a milling crowd of shouting, screaming people. He had already guessed what was happeningthis was a kindertransport, one of the trains hired to transport the ten thousand Jewish children that Britain had agreed to accept after Kristallnacht. The shriek had risen at the moment the guards started separating the children from their parents, and the two groups were now

being shoved apart by snarling brownshirts. Parents were backing away, tears running down their cheeks, as their children were herded onto the train, some waving frantically, some almost reluctantly, as if they feared to recognize the separation.

Further up the platform a violent dispute was underway between an SA Truppführer and a woman with a red cross on her sleeve. Both were screaming at the other, he in German, she in northern-accented English. The woman was beside herself with anger, almost spitting in the brownshirts eye, and it was obviously taking everything he had not to smash his fist into her face. A few feet away one of the mothers was being helped to her feet by another woman. Blood was streaming from her nose.

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave The Dark Clouds Shining

The Dark Clouds Shining Masaryk Station (John Russell)

Masaryk Station (John Russell) Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Zoo Station jr-1

Zoo Station jr-1 Masaryk Station

Masaryk Station One Man's Flag

One Man's Flag Potsdam Station jr-4

Potsdam Station jr-4 Stattin Station jr-3

Stattin Station jr-3 Masaryk Station jr-6

Masaryk Station jr-6 Silesian Station (2008) jr-2

Silesian Station (2008) jr-2 Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Silesian Station (2008)

Silesian Station (2008) The Moscow Option

The Moscow Option The Red Eagles

The Red Eagles Zoo Station

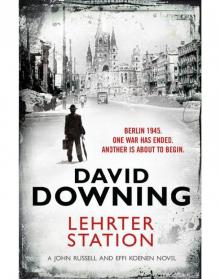

Zoo Station Lehrter Station

Lehrter Station Lehrter Station jr-5

Lehrter Station jr-5