- Home

- David Downing

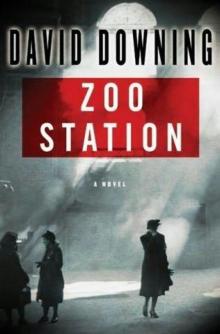

Zoo Stationee Page 17

Zoo Stationee Read online

Page 17

Come up, she said when they reached the lobby, and gave him a quick glance to make sure he hadnt read anything into the invitation.

Her suite was modest, but a suite just the same. An open suitcase sat on the bed, half-filled with clothes, surrounded by bits and pieces. Ill only be a minute, she said, and disappeared into the bathroom.

An item on the bed had already caught Russells eyeone of the small gray canvas bags that the Kripo used for storing personal effects.

There was no sound from the bathroom. Now or never, he told himself.

He took one stride to the bed, loosened the string, and looked inside the bag. It was almost empty. He poured the contents onto the bed and sorted through them with his fingers. A reporters notebookalmost empty. German notesalmost 300 Reichsmarks worth. McKinleys press accreditation. His passport.

The toilet flushed.

Russell slipped the passport into his pocket, rammed the rest back into the bag, tightened the string, and stepped hastily away from the bed.

She came out of the bathroom, looked at the mess on the bed, staring, or so it seemed to Russell, straight at the bag. She reached down, picked it up . . . and placed it in the suitcase. I thought wed eat here, she said.

FIVE MINUTES LATER, they were being seated in the hotel restaurant. Having locked her brother away in some sort of emotional box, she chatted happily about America, her dog, the casting of Vivien Leigh as Scarlett OHara in the new film of Gone with the Wind. It was all very brittle, but brittle was what she was.

After they had eaten he watched her look around the room, and tried to see it through her eyes: a crowd of smart people, most of the women fashionably dressed, many of the men in perfectly tailored uniforms. Eating good food, drinking fine wines. Just like home.

Do you think therell be a war? she asked abruptly.

Probably, he said.

But what could they gain from one? she asked, genuinely puzzled. I mean, you can see how prosperous the country is, how content. Why risk all that?

Russell had no wish to talk politics with her. He shrugged agreement with her bewilderment and asked how the flight across the Atlantic had been.

Awful, she said. So noisy, though I got used to that after a while. But its a horrible feeling, being over the middle of the ocean and knowing that theres no help for thousands of miles.

Are you going back the same way?

Oh no. It was Daddy who insisted I come that way. He thought it was important that I got here quickly, though I cant imagine why. No, Im going back by ship. From Hamburg. My train leaves at three, she added, checking her watch. Will you take me to the station?

Of course.

Upstairs he watched her cram her remaining possessions into the suitcase, and breathed a silent sigh of relief when she asked him to close it for her. A taxi took them to the Lehrter Bahnhof, where the D-Zug express was already waiting in its platform, car attendants hovering at each door.

Thank you for your help, she said, holding out a hand.

Im sorry about the circumstances, Russell said.

Yes, she agreed, but more in exasperation than sadness. As he turned away she was reaching for her cigarettes.

Near the front of the train three porters were manhandling a coffin into the baggage car. Russell paused in his stride, and watched as they set it down with a thump by the far wall. Show some respect, he felt like saying, but what was the point? He walked on, climbing the steps to the Stadtbahn platforms which hung above the mainline stations throat. A train rattled in almost instantly, and three minutes later he was burrowing down to the U-bahn platforms at Friedrichstrasse. He read an abandoned Volkischer Beobachter on the journey to Neukölln, but the only item of interest concerned the Party student leader in Heidelberg. He had forbidden his students from dancing the Lambeth Walka jaunty Cockney dance, recently popularized on the London stageon the grounds that it was foreign to the German way of life, and incompatible with National Socialist behavior.

How many Germans, Russell wondered, were itching to dance the Lambeth Walk?

Not the family in Zembskis studio, that was certain. They were there to have their portrait taken, the father in SA uniform, the wife in her church best, the three blond daughters all in pigtails, wearing freshly ironed BdM uniforms. Nazi heaven.

Russell watched as the big Silesian lumbered around, checking the lighting and the arrangement of the fake living room setting. Finally he was satisfied. Smile, he said, and clicked the shutter. One more, he said, and smile this time. The wife did; the girls tried, but the father was committed to looking stern.

Russell wondered what was going through Zembskis mind at moments like this. He had only known the Silesian for a few years, but hed heard of him long before that. In the German communist circles which he and Ilse had once frequented, Zembski had been known as a reliable source for all sorts of photographic services, and strongly rumored to be a key member of the Pass-Apparat, the Berlin-based Comintern factory for forged passports and other documents. Russell had never admitted his knowledge of Zembskis past. But it was one of the reasons why he used him for his photographic needs. That and the fact that he liked the man. And his low prices.

He watched as Zembski ushered the family out into the street with promises of prints by the weekend. Closing the door behind them he rolled his eyes toward the ceiling. Is smiling so hard? he asked rhetorically. But of course, hell love it. I only hope the wife doesnt get beaten to a pulp for looking happy. He walked across to the arc lights and turned them off. And what can I do for you, Mister Russell?

Russell nodded toward the small office which adjoined the studio.

Zembski looked at him, shrugged, and gestured him in. Two chairs were squeezed in on either side of a desk. I hope its pornography rather than politics, he said once they were inside. Though these days its hard to tell the difference.

Russell showed him McKinleys passport. I need my photograph in this. I was hoping youd either do it for me or teach me how to do it myself.

Zembski looked less than happy. What makes you think Id know?

I was in the Party myself once.

Zembskis eyebrows shot up. Ah. A lots changed since then, my friend.

Yes, but theyre probably still using the same glue on passports. And you probably remember which remover to use.

Zembski nodded. Not the sort of thing you forget. He studied McKinleys passport. Who is he?

Was. Hes the American journalist who jumped in front of a train at Zoo Station last weekend. Allegedly jumped.

Better and better, the Silesian said dryly. He opened a drawer, pulled out a magnifying glass, and studied the photograph. Looks simple enough.

Youll do it?

Zembski leaned back in his chair, causing it to squeak with apprehension. Why not?

How much?

Ah. That depends. Whats it for? I dont want details, he added hurriedly, just some assurance that it wont end up on a Gestapo desk.

I need it to recover some papers. For a story.

Not a Führer-friendly story?

No.

Then Ill give you a discount for meaning well. But itll still cost you a hundred Reichsmarks.

Fair enough.

Cash.

Right.

Ill take the picture now then, Zembski said, maneuvering his bulk out of the confined space and through the door into the studio. A plain background, he muttered out loud as he studied the original photograph. Thisll do, he said, pushing a screen against a wall and placing a stool in front of it.

Russell sat on it.

Zembski lifted his camera, tripod and all, and placed it in position. After feeding in a new film, he squinted through the lens. Try and look like an American, he ordered.

How th

e hell do I do that? Russell asked.

Look optimistic.

Ill try. He did.

I said optimistic, not doe-eyed.

Russell grinned, and the shutter clicked.

Lets try a serious one, Zembski ordered.

Russell pursed his lips.

The shutter clicked again. And again. And several more times. Thatll do, the Silesian said at last. Ill have it for you on Monday.

Thanks. Russell stood up. One other thing. You dont by any chance know of a good place to pick up a secondhand car?

Zembski dida cousin in Wedding owned a garage which often had cars to sell. Tell him I sent you, he said, after giving Russell directions, and you may get another discount. We Silesians are all heart, he added, chins wobbling with merriment.

Russell walked the short distance back to the U-bahn, then changed his mind and took a seat in the shelter by the tram stop. Gazing back down the brightly lit Berlinerstrasse toward Zembskis studio, he wondered whether hed just crossed a very dangerous line. No, he reassured himself, all hed done was commission a false passport. He would cross the line when he made use of it.

AFTER TEACHING THE WIESNER girls the next morning, Russell headed across town in search of Zembskis cousin. He found the garage on one of Weddings back streets, sandwiched between a brewery and the back wall of a locomotive depot, about half a kilometer from the Lehrter Station. Zembskis cousin Hunder was also a large man, and looked a lot fitter than Zembski. He seemed to have half a dozen young men working for him, most of them barely beyond school age.

The cars for sale were lined around the back. There were four of them: a Hanomag, an Opel, a Hansa-Lloyd, and another Opel. Any color you want as long as its black, Russell murmured.

We can re-spray, Hunder told him.

No, blacks good, Russell said. The more anonymous the better, he thought. How much are they? he asked.

Hunder listed the prices. Plus a ten percent discount for a friend of my cousin, he added. And a full tank. And a months guarantee.

The larger Hansa-Lloyd looked elegant, but was way out of Russells monetary reach. And he had never liked the look of Opels.

Can I take the Hanomag out for a drive? he asked.

You do know how? Hunder inquired.

Yes. He had driven lorries in the War, and much later he and Ilse had actually owned a car, an early Ford, which had died ignominiously on the road to Potsdam soon after their marriage met a similar fate.

He climbed into the driving-seat, waved the nervous-looking Hunder a cheerful goodbye, and turned out of the garage yard. It felt strange after all those years, but straightforward enough. He drove up past the sprawling Lehrter goods yards, back through the center of Moabit, and up Invalidenstrasse. The car was a bit shabby inside, but it handled well, and the engine sounded smooth enough.

He stopped by the side of the Humboldt canal basin and wormed his way under the chassis. There was a bit of rust, but not too much. No sign of leakages, and nothing seemed about to fall off. Brushing himself down, he walked around the vehicle. The engine compartment looked efficient enough. The tires would need replacing, but not immediately. The lights worked. It wasnt exactly an Austro-Daimler, but it would have to do.

He drove back to the garage and told Hunder hed take it. As he wrote out the check, he reminded himself how much hed be saving on tram and train tickets.

It was still early afternoon as he drove home, and the streets, with the exception of Potsdamerplatz, were relatively quiet. He parked in the courtyard, and borrowed a bucket, sponge, and brush from an excited Frau Heidegger. She watched from the step as he washed the outside and cleaned the inside, her face full of anticipation. A quick drive, he offered, and she needed no second bidding. He took them through Hallesches Tor and up to Viktoria Park, listening carefully for any sign that the engine was bothered by the gradient. There was none. I havent been up here for years, Frau Heidegger exclaimed, peering through the windshield at the Berlin panorama as they coasted back down the hill.

Effi was just as excited a couple of hours later. Her anger at his late arrival evaporated the moment she saw the car. Teach me to drive, she insisted.

Russell knew that both her father and ex-husband had refused to teach her, the first because he feared for his car, the second because he feared for his social reputation. Women were not encouraged to drive in the new Germany. Okay, he agreed, but not tonight, he added, as she made for the drivers seat.

It was a ten-minute drive to the Conways modern apartment block in Wilmersdorf, and the Hanomag looked somewhat overawed by the other cars parked outside. Dont worry, Effi said, patting its hood. We need a name, she told Russell. Something old and reliable. How about Hindenburg?

Hes dead, Russell objected.

I suppose so. How about Mother?

Mine isnt reliable.

Oh all right. Ill think about it.

They were the last to arrive. Phyllis Conway was still putting the children to bed, leaving Doug to dispense the drinks. He introduced Russell and Effi to the other three couples, two of whomthe Neumaiers and the Auerswere German. Hans Neumaier worked in banking, and his wife looked after their children. Rolf and Freya Auer owned an art gallery. Conways replacement, Martin Unsworth, and his wife Fay made up the third couple. Everyone present, Russell reckoned, either was approaching, was enjoying or had recently departed their thirties. Hans Neumaier was probably the oldest, Fay Unsworth the youngest.

Effi disappeared to read the children a bedtime story, leaving Russell and Doug Conway alone by the drinks table. I asked the Wiesners, Conway told him. I went out to see them. He shook his head. They were pleased to be asked, I think, but they wouldnt come. Dont want to risk drawing attention to themselves while theyre waiting for their visas, I suppose. They speak highly of you, by the way.

Is there nothing you can do to speed up their visas?

Nothing. Ive tried, believe me. Im beginning to think that someone in the system doesnt like them.

Why, for Gods sake?

I dont know. Ill keep trying, but. . . . He let the word hang. Oh, he said, reaching into his jacket pocket and pulling out two tickets. I was given these today. Brahms and something else, at the Philharmonie, tomorrow evening. Would you like them? We cant go.

Thanks. Effill be pleased.

Whats she doing now? Barbarossa has finished, hasnt it?

Yes. But youd better ask her about the next project.

Conway grinned. I will. Come on, wed better join the others.

The evening went well. The conversation flowed through dinner and beyond, almost wholly in German, the two Conways taking turns at providing translation for Fay Unsworth. The two German men were of a type: scions of upper middle class families who still prospered under the Nazis but who, in foreign company especially, were eager to demonstrate how embarrassed they were by their government. They and Freya Auer lapped up Effis account of the Mother storyline, bursting into ironic applause when she described the hospital bed denouement. Only Ute Neumaier looked uncomfortable. Among her fellow housewives in Grunewald she would probably give the story a very different slant.

Rolf Auer was encouraged to recount some news hed heard that afternoon. Five of Germanys most famous cabaret comediansWerner Finck, Peter Sachse, and the Three Rulandshad been expelled from the Reich Cultural Chamber by Goebbels. They wouldnt be able to work in Germany again.

When was this announced? Russell asked.

It hasnt been yet. Goebbels has a big piece in the Beobachter tomorrow morning. Its in there.

Last time I saw Finck at the Kabarett, Russell said, he announced that the old German fairytale section had been removed from the program, but that thered be a political lecture later.

/> Everyone laughed.

Itll be hard for any of them to get work elsewhere, Effi said. Their sort of comedys all about language.

Theyll have to go into hibernation until its all over, Phyllis said.

Like so much else, her husband agreed.

Where has all the modern art gone? Effi asked the Auers. Six years ago there must have thousands of modern paintings in Germanythe Blau Reiter group, the Expressionists before them, the Cubists. Where are they all?

A lot of them are boxed up in cellars, Rolf Auer admitted. A lot were taken abroad in the first year or so, but since then. . . . A lot were owned by Jews, and most of those have been sold, usually at knockdown prices. Mostly by people who think theyll make a good profit one day, sometimes by people who really care about them as art and want to preserve them for the future.

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave The Dark Clouds Shining

The Dark Clouds Shining Masaryk Station (John Russell)

Masaryk Station (John Russell) Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Zoo Station jr-1

Zoo Station jr-1 Masaryk Station

Masaryk Station One Man's Flag

One Man's Flag Potsdam Station jr-4

Potsdam Station jr-4 Stattin Station jr-3

Stattin Station jr-3 Masaryk Station jr-6

Masaryk Station jr-6 Silesian Station (2008) jr-2

Silesian Station (2008) jr-2 Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Silesian Station (2008)

Silesian Station (2008) The Moscow Option

The Moscow Option The Red Eagles

The Red Eagles Zoo Station

Zoo Station Lehrter Station

Lehrter Station Lehrter Station jr-5

Lehrter Station jr-5