- Home

- David Downing

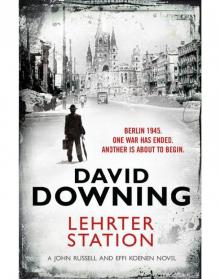

Lehrter Station Page 2

Lehrter Station Read online

Page 2

After alighting on Highgate Road she said as much to Russell.

‘The portrayal of women,’ he guessed. ‘Though the men were just as appalling. The only sympathetic character was the younger sister, and they killed her off.’

‘There was also the friend, but she was too smart to attract a good man.’

‘True.’

The fog seemed thicker than ever, but perhaps it was the added smoke from the nearby engine sheds.

‘But you’re right,’ Effi went on, as they turned into Lady Somerset Road, ‘it was the way the women were written. When the Nazis were portraying them as submissive idiots, it was so wonderful to see someone like Katherine Hepburn show how happy and sexy independent women could be. And now the Nazis are gone, and Hollywood gives us Mildred, who can only have a successful career if she fails as a mother and husband. Goebbels would have loved it.’

‘A bit harsh,’ Russell murmured.

‘Not at all,’ she rounded on him. ‘You just…’

Two figures suddenly emerged in front of them, silhouettes in the mist. ‘Stick ’em up,’ one of the two said, in a tone that seemed borrowed from an American gangster movie.

‘What?’ was Russell’s first reaction. The voice sounded young, and both potential robbers seemed unusually short. But it did look like a real gun pointing at them. A Luger, if Russell was not mistaken.

‘Stick ’em up,’ the voice repeated petulantly. The faces were becoming clearer now – and they belonged to boys, not men. Fourteen perhaps, maybe even younger. The one on the left was wearing trousers too long for his legs. A relation who hadn’t come home.

‘What do you want?’ Russell asked, with what felt like remarkable good humour, given the situation. Only that morning he’d read about two thirteen-year-olds holding up a woman in Highgate. Far too many boys had lost their fathers.

‘Your money of course,’ the second boy said, almost apologetically.

‘We only have a couple of shillings.’

‘You Germans are all liars,’ the first boy said angrily.

‘I’m English,’ Russell patiently explained, as he reached inside his coat pocket for the coins in question. He doubted the gun was even loaded, but it didn’t seem worth the risk to find out.

Effi had other ideas. ‘This is ridiculous,’ she muttered in German, as she stepped forward and twisted the gun out of the surprised youth’s hand. ‘Now go home,’ she told them in English.

They glanced at each other, and bolted off into the fog.

Effi just stood there, amazed at what she’d done. She was, she realised, shaking like a leaf. What mad instinct had made her do such a thing?

‘Christ almighty,’ Russell exclaimed, reaching out for her. ‘For a moment there…’

‘I didn’t think,’ she said stupidly. She started to laugh, but there was no humour in the sound, and Russell cradled her head against his shoulder. They stood there for a while, until Effi disentangled herself and offered him the gun.

He put it in his coat pocket. ‘I’ll hand it in at the police station tomorrow morning.’

They walked the short distance home, and let themselves in to the ground floor flat that Russell had rented. It had two large rooms, a small kitchen and an outside toilet. Russell, Effi and Rosa shared the back room, Paul, Lothar and Zarah the curtain-divided room at the front. Other families of four and five lived above and below them.

Paul was reading a book on architecture in the kitchen, his English dictionary propped up beside him. ‘They’re all asleep,’ he told them quietly.

Effi went to check on Rosa, the young Jewish orphan who had been her ward since April. Though perhaps not an orphan, as Effi reminded herself. The father Otto had disappeared around 1941, and not been seen or heard of since. He was probably dead, but there was no way of knowing for sure. Effi thought the uncertainty worried Rosa – it certainly worried her.

Sitting down on the side of the bed, she could smell the Vick’s Vapo-Rub that Zarah had put on the girl’s chest. Effi pulled the blanket up around her neck, and told herself that Rosa was coping better than most with the post-war world. She was doing well at the school that Solly had found for them. Although there were many other refugee pupils, the instruction was wholly in English, and Rosa’s command of that language was already better than Effi’s own. And Solly seemed more excited by her Berlin drawings than by any of John’s ideas. The girl would end up supporting them both.

In the kitchen, Russell was telling his son about the attempted hold-up. Paul’s smile vanished when he realised his father wasn’t having him on. ‘Was the gun loaded?’ he asked.

‘I haven’t looked,’ Russell admitted, and pulled it from his pocket. ‘It was,’ he discovered. ‘I’ll put it out of harm’s way,’ he added, reaching up to place it on the highest shelf. ‘Anything interesting happen at work?’

‘Not really,’ Paul said, getting up. ‘It’s time I went to bed,’ he explained. ‘Another early start.’

‘Of course,’ Russell said automatically. His son didn’t want to talk to him, which was neither unusual nor intended personally: Paul didn’t want to talk to anybody. But he seemed to be functioning like a normal human being – only that lunchtime Solly had confided how pleased he was with the boy – and Russell knew from experience what havoc war could wreak on minds of any age. ‘Sleep well,’ he said.

‘I hope so,’ Paul said. ‘For everyone’s sake,’ he added wryly – his nightmares sometimes woke the whole house. ‘Oh, I forgot,’ he added, stopping in the doorway. ‘There was a letter for you. It’s on your bed.’

‘I’ve got it,’ Effi said, squeezing past him. She gave Paul a goodnight hug before handing the envelope over to Russell.

He tore it open, and extracted the contents – a short handwritten note and a grandstand ticket for the following Tuesday’s match between Chelsea and the Moscow Dynamo tourists. ‘Your attendance is expected,’ the note informed him. It was signed by Yevgeny Shchepkin, his erstwhile guardian angel in Stalin’s NKVD.

‘So the bill has finally arrived,’ Effi said, reading it over his shoulder.

Lying beside her half an hour later, Russell felt strangely pleased that it had. In May he had bought his family’s safety from the Soviets with atomic secrets and vague promises of future service, and he had always known that one day they would demand payment on the Faustian bargain. For months he had dreaded that day, but now that it was here, he felt almost relieved.

It wasn’t just an end to the suspense. The war in Europe had been over for six months, and the Nazis, who had dominated their lives for a dozen years, were passing into history, but all their lives – his and Effi’s in particular – had still seemed stuck in some sort of post-war limbo, the door to their future still locked by their particular past. And Shchepkin’s invitation might – might – be the key that would open it.

* * *

Monday morning was unusually crisp and clear, columns of smoke rising from a hundred chimneys into a clear blue sky as Russell walked down Kentish Town Road. There were long lines outside the two bakeries he passed, but most of the queuing women seemed happy to chat while they waited.

It had been a strange weekend. On Saturday morning he had taken the gun to the local police station, and been asked to peruse an alarmingly extensive array of juvenile mug shots. He hadn’t recognised his and Effi’s would-be robbers, who had presumably just set out on their new career of crime.

That afternoon the whole family had gone for a walk on the nearby Heath, but their collective mood had matched the grey weather. Paul and Lothar kicked around the latter’s new football – one of Zarah’s acquisitions from their street’s resident spiv – but only the youngster looked like he was enjoying the experience. Effi still seemed subdued by the previous evening’s excitement, and Rosa, as usual, responded to her new mother’s mood. Only Zarah seemed determined to be cheerful, and after what she’d been through with the Russians – repeatedly raped by a Red Army foursome for three

days and nights – Russell could only admire her for that.

Sunday the rain had come down, and they’d tiptoed around each other in the crowded flat, waiting for the weekend to end.

At least today was fine, and the long walk into town could be enjoyed for more than the saving of the bus fare. It took him half an hour to reach the Corner House opposite Tottenham Court Road tube station, where he had lately taken to having his morning coffee. It was a far cry from Kranzler’s in Berlin – the decor was dreadful, the coffee worse – but a ritual was a ritual. A journalist had to read the papers somewhere, even one who was out of work, and he had grown used to the Corner House’s heady blend of non-stop bustle, sweat and steam.

As usual, he began with the more digestible News Chronicle. Remembering he would soon see them play, he sought out the latest news of the Soviet footballers. The Sunday papers had been unimpressed – one witness of a training session at the White City had deemed them ‘so slow that you can hear them think’ – and the Monday Chronicle seemed of similar mind. Russell didn’t know what to expect. Stalin’s Russia seemed an unlikely source of imaginative football, but the English had a notorious propensity to over-estimate their own prowess. It would be interesting, if nothing more. A nice sugar-coating for whatever pill the Soviets had decided he should swallow.

The rest of the paper held no surprises. There was advice for demobbed husbands returning home – ‘be glad to be back, say so as often you can’ – and another child drowned in an emergency water tank. In Yorkshire three young women had been sacked from their jobs for refusing to swap their slacks for skirts.

The front page was full of the Prime Minister’s visit to Washington. Attlee was apparently asking the Americans to share their atomic secrets with the Russians, and their wealth with an impoverished Britain. The Americans seemed more interested in persuading him to abandon his policy of imposing restrictions on Jewish emigration to Palestine.

There was nothing to match Russell’s favourite revelation of the last few days, that Eva Braun’s father had written to Hitler before the war, demanding to know the Führer’s intentions. Having never received a reply, Herr Braun now believed that his letter had not reached its intended recipient.

What other explanation could there be?

Turning to the weightier Times, Russell found some Berlin news. A ‘Battle of Winter’ had been proclaimed, which sounded rather ominous, and involved cannibalising badly damaged buildings for those with a better chance of being patched up. Meanwhile owners of slightly damaged buildings had been given a year to claim compensation. This would interest Effi, whose building on Carmerstrasse had still been essentially intact when they last saw it.

The Soviets had celebrated the anniversary of Lenin’s revolution by handing out gifts: a small sack of coal for each human resident, and extra food for the lions, elephant and hyena who had survived the shelling of the Zoo. And should this seem like small change for raping half the city’s women, they had also unveiled a memorial to the liberating army. Anyone expecting a keener sense of irony from the nation of Gogol would be disappointed.

It was almost time for his meeting with Solly. Leaving the Corner House, he walked down Charing Cross Road, checking the windows for any new books. Solly Bernstein’s office on Shaftesbury Avenue had survived the Blitz, but the ground floor steam laundry of pre-war days was now an insurance office. Russell walked up the four flights of stairs to the second floor, paused to recover his breath, and let himself in. Solly had a receptionist these days – a waif-like Hungarian refugee named Marisa with dark, frightened eyes and a very basic grasp of English. Told that Mr Bernstein was ‘engage-ed’, Russell found his son in the smaller of the two back rooms, bent over what looked like the firm’s accounts. Given Paul’s emotional state at the time, Solly’s offer of a job had been somewhat charitable, but the boy seemed to be managing all right. And his English had improved no end.

The two of them talked football while Russell waited for Solly, and Paul expressed an interest in seeing the Russians’ second game in London, against the Arsenal. The Gunners’ bomb-damaged ground at Highbury was still under repair, so they were hosting the Dynamos at nearby White Hart Lane on the following Wednesday.

He’d try and get some tickets, Russell told his son. He could ask Shchepkin when he saw him at Stamford Bridge.

Marisa put her head round the door, smiled sweetly at Paul, and told Russell he could now see Solly. The agent’s news proved as bad as Russell had expected – all his recent ideas for feature articles had been rejected. Solly himself looked older than usual, his hair a little greyer, his eyes a little duller. As usual, he spent ten minutes telling Russell that he should take a break from journalism, and use the time to write a book. His escape from Germany in December 1941, Effi’s adventures with the Berlin resistance – either, in Solly’s not-so-humble opinion, would sell like fresh bagels. He was probably right, but the idea was still unappealing. Russell was a journalist, not a writer. And while an unsuccessful book would do nothing for his finances, a successful one might raise his profile to a dangerous degree. And what would he live on while he wrote it?

He said goodbye to Paul, walked back down to the street, and stood on the pavement outside wondering what to do with the rest of the day. More walking, he supposed, and set off in the general direction of the river. If the Soviets had no immediate plans for him perhaps he would give the book a try; at least he would be doing something. The world of journalism certainly seemed closed to him. The British nationals and London locals had no vacancies, and should one arise his American citizenship – acquired to allow his continued residence in Germany once Britain and the Reich were at war – was bound to complicate matters. As were other chunks of his personal history. His time living in Nazi Germany made the left suspicious, and his former membership of both British and German communist parties had a similar effect on those with right-wing sympathies. If editors needed a further excuse for rejecting him, they could always point to his long exile and its obvious corollary, that he was out of touch with British life. Russell always denied this, but without much inner conviction. He did often feel a stranger in the land of his birth and childhood. If he wanted to function as a journalist again, then Berlin was the place to do so.

But Berlin, as The Times had told him only that morning, was still on its knees. His extended family had already experienced a stunning variety of traumas in that city, and taking them back for more seemed almost sadistic.

He walked on across Trafalgar Square, down the other side of Charing Cross Station to the Embankment, and slowly up past Cleopatra’s Needle and the Savoy Hotel towards the new Waterloo Bridge. He, Paul, Zarah and Lothar had stayed at the Savoy in 1939; they had come to see a wellknown Scottish paediatrician, in the hope of allaying Zarah’s fears that Lothar was in some way mentally handicapped. Russell had been their chaperone and interpreter, and a tour guide to his eleven year-old son.

It had been a wonderful couple of days. Lothar had been given a clean bill of mental heath; he and Paul had seen a match at Highbury, inspected the streamlined Coronation Scot at Euston, and walked past Bow Street Police Station, where the fictional Saint’s sparring partner Chief Inspector Teal had his office. In the bar of the Savoy, an idiot from the War Office had tried to persuade Russell that risking his life for His Majesty’s Government was the very least he could do.

And that was the other complicating factor, Russell thought, as he leaned his midriff against the railings and looked down at the swirling brown waters – his mostly unresolved relationships with the world’s leading intelligence agencies. Between 1939 and 1941 he had performed, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, services for the Soviets, Americans, British and Germans. Getting into this world had been all too easy, extracting himself wholly beyond him. He had concentrated on surviving the war with a more or less functioning conscience, and just about succeeded. But there was no way of breaking the bond, no way to wipe the slate clean.

The Nazis

at least were gone. He had worked for them under duress, and as far as he knew had never done anything actually helpful, but there was always the chance of accusations that only the dead could refute. The British had ignored him since 1939, the Americans since 1942, but Russell doubted whether their indifference would survive a return to Berlin. He was of no use to them in London, but his many contacts in the German capital – on both sides of the new political divide – would make him a valuable asset.

The Soviets, though, were the real danger. In May he had secured his family’s exit from Berlin and Germany by leading the NKVD to the cache of German atomic energy documents which he and the young Soviet physicist Varennikov had stolen from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Reasoning that the Soviets might be tempted to ensure his permanent silence on this matter, he had forcibly reminded them that he couldn’t tell the Americans anything without incriminating himself. The Soviets had probably already realised as much, and soon made it clear that they would use the threat of revelation to force Russell’s cooperation in whatever future ventures seemed appropriate.

It was an effective threat. Neither the Soviets nor Russell knew how the Americans would respond should the story of his theft of the atomic papers become public, but Russell had reason to fear the worst. Another wave of anti-communist hysteria was building in the US, and an American citizen putting family above country when it came to atomic secrets might well end up in the electric chair. At the absolute best, he would never get another job with an American – or British – newspaper.

And now the Soviets had come calling. What would they want this time? Whatever it was, it would probably involve a return to Berlin, and another separation from his son and Effi.

Paul was still in bad shape, but Russell suspected that there was little he could offer in the way of help, that the boy had to find his own road back. And there were signs, every now and then, that he was doing just that. It might be wishful thinking, but he thought his son would eventually work out how best to live with his past.

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave The Dark Clouds Shining

The Dark Clouds Shining Masaryk Station (John Russell)

Masaryk Station (John Russell) Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Zoo Station jr-1

Zoo Station jr-1 Masaryk Station

Masaryk Station One Man's Flag

One Man's Flag Potsdam Station jr-4

Potsdam Station jr-4 Stattin Station jr-3

Stattin Station jr-3 Masaryk Station jr-6

Masaryk Station jr-6 Silesian Station (2008) jr-2

Silesian Station (2008) jr-2 Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Silesian Station (2008)

Silesian Station (2008) The Moscow Option

The Moscow Option The Red Eagles

The Red Eagles Zoo Station

Zoo Station Lehrter Station

Lehrter Station Lehrter Station jr-5

Lehrter Station jr-5