- Home

- David Downing

Masaryk Station jr-6 Page 2

Masaryk Station jr-6 Read online

Page 2

He looked at his watch and heaved himself back up-he had a meeting with a source that evening, and was hungry enough to eat dinner first. There was still no one on the desk downstairs, and the drunken English private hovering in the doorway was looking for a less salubrious establishment. Russell gave him directions to the Piazza Cavana, and watched the man weave unsteadily off down the cobbled street. Removing his trousers without falling over was likely to prove a problem. The restaurants on the Villa Nuova were already doing good business, with some hardy souls sitting out under the stars with their coats buttoned up. Russell found an inside table, ordered pollo e funghi, and sat there eating buttered ciabatta with his glass of Chianti, remembering his and Effi’s favourite trattoria on Ku’damm, back when the Nazis were just a bad dream.

An hour or so later, he was back in the Old City, climbing a narrow winding street toward the silhouetted castle. A stone staircase brought him to the door of a run-down delicatessen, whose back room doubled as a restaurant. There were only four tables, and only one customer-a man of around forty, with greased-back black hair and dark limpid eyes in a remarkably shiny face. He wore a cheap suit over a collarless shirt, and looked more than ready to play himself in a Hollywood movie.

‘Meester Russell,’ the man said, rising slightly to offer his hand after wiping it on a napkin. A plate with two thoroughly stripped chicken bones sat on the dirty tablecloth, along with a half-consumed bottle of red wine.

‘Mister Artucci.’

‘Call me Fredo.’

‘Okay. I’m John.’

‘Okay, John. A glass,’ he called over his shoulder, and a young woman in a grey dress almost ran to the table with one. ‘You can close now,’ Artucci told her, pouring wine for Russell. ‘My friend Armando tell me you interest in Croats. Father Kozniku, who run Draganovic’s office here in Trieste. Yes?’

Russell heard the woman let herself out, and close the door behind her. ‘I understand your girlfriend works in the office,’ he began. ‘I’d like to meet her.’

Artucci shook his head sadly. ‘Not possible. And I know everything from her. But money talks first, yes?’

‘Always,’ Russell wryly agreed, and spent the next few minutes patiently lowering the Italian’s grossly inflated expectations to something he could actually afford.

‘So what you know now?’ Artucci asked, lighting a cigarette that smelled even worse than Kuznakov’s brand.

Russell gave him a rundown. The whole business had come to his attention while on a fortnight’s secondment to the CIC office in Salzburg the previous year. The Americans, having decided not to prosecute a Croatian priest named Cecelja for war crimes, had started employing him as a travel operator for people they wanted out of Europe. As he investigated the latter over the next few months, it became clear to Russell that Cecelja, far from working alone, was just one cog of a much larger organisation, which was run from inside the Vatican by another Croatian priest named Krunoslav Draganovic. Using a whole network of priests, including Father Kozniku here in Trieste, Draganovic was selling and arranging passage out of Central and Eastern Europe for all sorts of refugees and fugitives.

The Americans called the whole business a ‘Rat Line’, but Russell doubted they knew just how varied the ‘rats’ had become. In addition to those thoroughly debriefed Soviet defectors whom the American CIC was set on saving from MGB punishment, Russell had so far identified fugitive Nazis, high-ranking Croat veterans of the fascist Ustashe, and a wide selection of all those Eastern European boys’ clubs which had clung to Hitler’s grisly bandwagon. The Americans were paying Draganovic $1,500 per person for their evacuees; but the others, for all he knew, were charity cases.

Artucci listened patiently, then blew out smoke. ‘So, what are your questions?’

‘Well, first off-are Draganovic and his people just in it for the money? Or are they politically motivated, using the money they get from the Americans to subsidise a service for their right-wing friends?’

‘Mmm,’ Artucci articulated, as if savouring the question’s complexity. ‘A little of both, I think. They like money; they don’t like communists. All same, in the end.’

‘That’s not very helpful,’ Russell told him, putting down a marker.

‘Well, what I say? I no see inside Draganovic mind. But Croat people he help-they kill for fifteen dollar. They only see fifteen hundred in dreams.’

‘Okay. So, as far as you know, have the Americans only bought exits for Soviet defectors and refugees? Or have they shelled out for Nazis and Ustashe as well?’ This was the key question in many ways. If the Americans, for whatever twisted political reasons, were helping certain war criminals escape Europe and justice, then he had a real story. Not one his American bosses in Berlin would want published, but with any luck at all they would never know the source. For more than a year now, Russell had been using a fictitious by-line for the stories which might upset one or both of his Intelligence employers, and the elusive Jakob Bruning was becoming one of European journalism’s more respected voices. As far as Russell knew, only Solly and Effi were aware that he and Bruning were one and the same.

Artucci was pondering his question. ‘Is difficult,’ he said at last. ‘How I say? All these people-the Americans, the British, Draganovic and his people-they all have agenda, yes? This Rat Line just one piece. I don’t know if Americans pay Draganovic for Nazis or Ustashe to escape, but they all talk to others-Americans here in Trieste; and British, they talk to Ustashe, give them guns. And everyone know they help Pavelic escape, everyone. Why they do that, if not to please his Krizari, the men they want to fight Tito and the Russians?’

He was probably right, Russell thought. It was hard to think of the Ustashe as acceptable allies in any circumstances-they had routinely committed atrocities the Nazis would have shrunk from-but, as Artucci said, the Allies had indeed spirited the appalling Ustashe leader Ante Pavelic away to South America. And what were the Americans’ current alternatives? When it came to potential allies, they were understandably-if somewhat foolishly-reluctant to put their faith in Social Democrats, which only left the parties of the tainted Catholic right. Nazi collaborators, fascists in all but name, but reliably anti-Communist. Everyone knew the Krizari-the Croat ‘Crusaders’-were Ustashe in fresh clothes, but as long as they took the fight to Tito, they had nothing to fear from the West.

Asked for names, Artucci grudgingly provided two-young men from Osijek with lodgings near the train station, who had been hanging around Kozniku’s office for the last week or so. They were waiting for something, Artucci thought. ‘And they pester my Luciana,’ he added indignantly. He offered to provide more names on a pro rata basis, provided Russell could guarantee his anonymity. ‘Some of these people, they think murder is nothing.’

But he didn’t seem worried as he walked off into the darkness, Russell’s dollars stuffed in his money-belt and a definite spring to his step. Russell gave him a start, then headed down the same street. Artucci was probably less informed than he thought he was, but he might well have his uses.

Reaching his hostel, Russell decided it was too early to shut himself away for the night, and continued on towards the seafront. Halfway along one narrow street, he became aware of footsteps behind him, and carefully quickened his pace before glancing over his shoulder. A man was following him, though whether deliberately was impossible to tell. There was no sign of hostile intent, and the footsteps showed no sign of quickening. Keeping his ears pricked, Russell kept walking, and eventually the man took a different turning. Russell sometimes got the feeling that putting the wind up strangers was a hobby among Triestinos.

He ended up, as usual, in the Piazza Unita. The city’s social hub boasted a well-kept garden with bandstand, and five famous cafes established in Habsburg times. Russell’s favourite was the San Marco, where writers had traditionally gathered. According to legend, James Joyce had worked on Ulysses at one corner table, from where he was frequently collected by his furious mistress, the

exquisitely named Nora Barnacle.

The cafe was about half-full. Russell ordered a nightcap, filched an abandoned Italian newspaper from an adjoining table, and idly glanced through its meagre contents. Nothing looked worth a laborious translation. When the small glass of ruby-red liquid arrived he sat there sipping, and thinking about the next day. Another eight hours of Kuznakov and his cigarettes, of Farquhar-Smith and Dempsey and their stupid questions. Russell didn’t know which he loathed the more-the Army intelligence types thrown up by the war, who had no idea what they were doing, or the new professionals now making their mark in Berlin, who were too dead inside to know why or what for.

Russell was nursing an almost empty glass when the door swung wide to reveal a familiar figure. Yevgeny Shchepkin looked around the room, betrayed with only the faintest curl of his lips that he’d noticed Russell, and took a seat at the nearest empty table before removing his hat and gloves. A waiter hurried towards him, took his order, and returned a few minutes later with a cup of espresso. Taking a sip, the white-haired Russian made eye contact for the first time. As he lowered the cup a slight movement of the head suggested they meet outside.

Russell sighed. He hadn’t expected to see Shchepkin here in Trieste, but the Russian had a habit of appearing at his shoulder, both physically and metaphorically. He rarely brought good news but, for reasons he never found quite convincing, Russell was fond of the man. Their fates had been intertwined for almost a decade now, first in working together against the Nazis, and then in a mutual determination to escape the Soviet embrace. His family in Moscow were hostages to Shchepkin’s continued loyalty, while Russell was constrained by Soviets threats to reveal his help in securing them German atomic secrets. As far as Stalin and MGB boss Lavrenti Beria were concerned, Russell was a Soviet double-agent, Shchepkin his control. As far as the Americans were concerned, the reverse was the case. All of which gave Russell and Shchepkin some latitude-helping ‘the enemy’ could always be justified as part of the deception. But it also tied them into the game that they both wanted out of.

After paying his check Russell wandered out into the square. A British army lorry was rumbling past on the seafront, offering material support to the Union Jack that fluttered from the top of the bandstand. The sky was clear, the temperature still dropping, and he raised his jacket collar against the breeze flowing in from the sea.

Shchepkin appeared about five minutes later, buttoning up his coat. Russell had a sudden memory of a very cold day in Krakow, and the Russian scolding him, almost maternally, for not wearing a hat.

They shook hands, and began a slow circuit of the gardens.

‘Have you just come from Berlin?’ Russell asked in Russian.

‘Via Prague.’

‘How are things? In Berlin, I mean.’

‘Interesting. You remember the big shake-up last September? Someone at the top had the bright idea of merging the MGB and the GRU, so KI was set up. It felt like a bad idea then, and things have only gotten worse. These days nobody seems to know who they’re accountable to, or who they should be worrying about. Different groups have ended up trying to snatch the same people from the Western zones. Some of our people in Berlin recruited KI staff as informers without knowing who they were.’

Shchepkin was always exasperated by incompetence, even that of his enemies. ‘And the wider picture?’ Russell asked patiently. He hadn’t had the trials and tribulations of the Soviet intelligence machine in mind when asking his question.

‘Serious,’ Shchepkin said. ‘I think Stalin has decided to test the Americans’ resolve. It won’t be anything dramatic, just a push here, a push there, nothing worth going to war over. Just loosening their grip on the city, one finger at a time, until it drops into our hands.’

‘It won’t work,’ Russell argued, with more certainty than he felt. He didn’t doubt the Americans’ will to resist, just their ability to work out the how and when.

‘Let’s hope not,’ Shchepkin agreed. ‘We might both prove surplus to requirements if Stalin gets his way. But …’

A shot sounded in the distance, several streets away. This wasn’t an uncommon occurrence in Trieste, and rarely seemed to have fatal consequences.

‘You were saying?’

‘Ah. Your absence has been noticed, even by Tikhomirov. And young Schneider misses you greatly,’ he added wryly. ‘He suspects you’re prolonging your stay here for no great reason.’

‘You can tell Schneider I’m prolonging my stay here to avoid seeing him.’

‘I don’t …’

‘But the real reason is, they won’t let me go. So many of your countrymen are turning up here uninvited, and I’m the only person they have who can talk to them.’

‘I see. Well, maybe I can do something about that. A local volunteer, perhaps.’

‘It would help if your people stopped planting fakes among the real defectors. Kuznakov will probably keep me busy for the next week.’

‘Ah, you spotted him, did you?’ Shchepkin said, sucking in his thin cheeks and sounding like a gratified teacher. ‘You didn’t give him up, though? He’s an idiot anyway, and I can tell my people you helped smooth his passage. We need every success we can get.’

‘We do? I thought we were doing rather well.’

‘Well, Tikhomirov and Schneider don’t agree. They know that building your credit with the Americans requires the occasional sacrifice of one of their own, but they still don’t like doing it, and they need the occasional reminder that your uses extend to the here and now.’

‘All right. But getting back to the original topic-the Americans are sending me to Belgrade in a couple of weeks, so Berlin will have to wait at least that long.’

Shchepkin was interested. ‘What do they want you to do there?’

‘They’re still deciding. As a journalist, they want me to sound out who I can, find out how real the row is between Tito and Stalin. But if past experience is any guide, they’ll also have a list of people they want me to contact. Potential allies, if they have any left, that is.’

Shchepkin was silent for a few moments. ‘There’s not much difference between journalism and espionage,’ he said eventually, sounding almost surprised.

‘One is illegal,’ Russell reminded him.

‘True,’ Shchepkin acknowledged. ‘Needless to say, we’d like copies of any reports. And there may be people we want you to see. I’ll let you know.’

‘Sounds ominous. If Tito and Stalin really have fallen out, then my Soviet “Get out of jail free” card won’t be worth much.’

‘Your what?’

‘It’s a board game called Monopoly,’ Russell explained. ‘If you land on a particular square, you end up in jail. But if you already have a “Get out of jail free” card you’re released straight away.’

‘Fascinating. And what’s the object of this game?’

‘Bankrupting your opponents by buying up properties and charging them rent each time they land on one.’

‘How wonderfully capitalistic.’

‘Indeed. But returning to the point-I won’t be much use to Berlin if I’m stuck in a Belgrade prison.’

‘I’ll bear that in mind,’ Shchepkin said, with a smile. They had completed one circuit, and were halfway through a second. Away to their left, two British warships were silhouetted against the sea and sky. ‘I was in Prague a few days ago,’ Shchepkin said, surprising Russell. The Russian rarely volunteered information about himself or his other activities.

‘Not much fun?’ Russell suggested. The Communists had taken sole control only six or seven weeks earlier, and shortly thereafter the pro-Western foreign minister Jan Masaryk had allegedly jumped to his death from a window in the Czernin Palace. According to Buzz Dempsey, the borders had been effectively closed ever since, as the Party relentlessly tightened its hold.

‘You could say that,’ Shchepkin said.

‘I expected better of the Czechs.’

‘Why?’

‘You kno

w your Marx. An industrial society, rich in high culture-isn’t that supposed to be the seed-bed of socialism?’

‘Of course. But the Czechs have us to contend with, the peasant society that got there first. And the more civilised the country, the tighter we’ll need to screw down the lid.’

Shchepkin was right, Russell thought. It was the same everywhere. In Berlin his friend Gerhard Strohm was continually complaining that the Soviets were destroying the German communists’ chances of creating anything worthwhile.

‘Look,’ Shchepkin said, ‘I understand your reluctance to come back to Berlin …’

‘You do?’

‘I know what you were doing before you left; and you’re probably doing the same thing here. Neither side has been choosy about whom they recruited, and they’re getting less so with each passing month. Both have taken on a fair proportion of ex-Nazis. To retain your credibility as a double-agent, you have to offer up people on both sides-American agents to us, our agents to the Americans. But as far as I can tell, every last one you’ve betrayed has been an ex-Nazi. You’re still fighting the war.’

‘And what’s wrong with that?’ Russell wanted to know.

‘Two things,’ Shchepkin told him. ‘One, eventually each side will start wondering just how committed you are to fighting their new enemy. And two, you’ll soon be running out of Nazis. What will you do then?’

‘Whatever I have to, I suppose. I was hoping you’d conjure us out of all this before I reached that point. Three years ago you talked about uncovering a secret so appalling that it would work as a “Get out of Stalin’s reach” card. Didn’t some innocent birdwatcher accidentally take a photo of Beria pushing Masaryk out of his window, which we could use to blackmail the bastard?’

‘It was three in the morning.’

‘Pity.’

They both laughed.

‘We’ll meet again on Thursday,’ Shchepkin decided. ‘Here at the same time.’

It was almost midnight, but Russell still felt more restless than sleepy. He walked north up the seafront, passing groups of huddled refugees, and one suspicious stack of crates guarded by a posse of Jews-more guns for the Haganah’s war with the Arabs. Hitler had been dead for almost three years, but so many of the conflicts his war had engendered were still unresolved. A line from a long-forgotten poem came back to Russell: ‘War is just a word for what peace can’t conceal.’

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave The Dark Clouds Shining

The Dark Clouds Shining Masaryk Station (John Russell)

Masaryk Station (John Russell) Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Zoo Station jr-1

Zoo Station jr-1 Masaryk Station

Masaryk Station One Man's Flag

One Man's Flag Potsdam Station jr-4

Potsdam Station jr-4 Stattin Station jr-3

Stattin Station jr-3 Masaryk Station jr-6

Masaryk Station jr-6 Silesian Station (2008) jr-2

Silesian Station (2008) jr-2 Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Silesian Station (2008)

Silesian Station (2008) The Moscow Option

The Moscow Option The Red Eagles

The Red Eagles Zoo Station

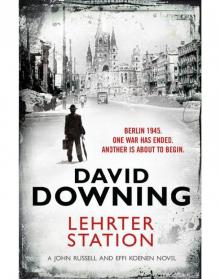

Zoo Station Lehrter Station

Lehrter Station Lehrter Station jr-5

Lehrter Station jr-5