- Home

- David Downing

Stattin Station jr-3 Page 2

Stattin Station jr-3 Read online

Page 2

The BBC news, when it came, was only mildly encouraging. On the Moscow front, the Germans had suffered a setback outside Tula, but the failure to mention any other sectors probably implied that the Wehrmacht was still advancing. The RAF had bombed several north German ports with unstated results, and the British army facing Rommel in North Africa was henceforth to be known as Eighth Army. What, Russell wondered, had happened to the other seven? The one piece of unalloyed good news came from Yugoslavia, where a German column had been wiped out by Serb partisans, and the German High Command had promised a retaliatory reign of terror. Some people never learned.

He switched the radio to a German station playing classical music and settled down with a book, eventually dozing off. The telephone woke him with a start. He picked up expecting to hear Effi, and an explanation of what had held her up. Had the air raid sirens gone off while he was asleep?

It wasn't her. 'Klaus, there's a game tonight,' a familiar voice told him. 'At number 26, ten o'clock.'

'There's no Klaus here,' Russell said. 'You must have got the wrong number.'

'My apologies.' The phone clicked off.

Russell pulled his much-creased map from his jacket pocket and counted out the stations on the Ringbahn, starting at Wedding and going round in a clockwise direction. As he had thought, Number 26 was Puttlitz Strasse.

It was gone half-past eight, which didn't leave him much time. After checking his street atlas he decided it was walkable, just. He wrote a hurried note to Effi, put on his thickest coat, and headed out.

The moon was rising, cream-coloured and slightly short of full, above the double-headed flak tower in the distant Tiergarten. He walked north at a crisp pace, hoping that there wouldn't be an air raid, and that if there was, he could escape the attentions of some officious warden insistent on his taking shelter. As the moon rose, the white-painted kerbstones grew easier to follow, and his pace increased. There were quite a few people out, most of them wearing one or more of the phosphorescent buttons which sprinkled the blackout with faint blue lights. Vehicles were much thinner on the ground, one lorry with slitted headlights passing Russell as he crossed the moon-speckled Landwehrkanal.

It was ten to ten when he reached the Puttlitz Strasse Station entrance, which lay on a long bridge across multiple tracks. Gerhard Strohm was waiting for him, chatting to the booking clerk in the still open S-Bahn ticket office. He was a tall, saturnine man with darting black eyes and a rough moustache. His hair was longer than the current fashion, and he was forever pushing back the locks that flopped across his forehead. Physically, and only physically, he reminded Russell of the young Stalin.

'Come,' Strohm told Russell, and led him back out across the road and down a flight of dangerously unlit steps to the yard below. As they reached the foot an electric S-Bahn train loomed noisily out of the dark, slowing as it neared the station.

'This way,' said Strohm, leading Russell into the dark canyon which lay between two lines of stabled carriages. His accent was pure Berliner, and anyone unaware of his background would have had a hard job believing that he'd been born in California of first-generation German immigrants. Both parents had been lost in a road accident when he was twelve, and young Gerhard had been sent back to his mother's parents in Berlin. Bright enough for university in 1929, his strengthening political convictions had quickly disqualified him from any professional career in Hitler's Germany. Arrested in 1933 for a minor offence, he had served a short sentence and effectively gone underground on his release. For the last seven years he had earned a living as a dispatcher in the Stettin Station goods yards.

Russell assumed Strohm was a communist, although the latter had never claimed as much. He often sounded like one, and he had got Russell's name from a comrade, the young Jewish communist Wilhelm Isendahl, whose life had intersected with Russell's for a few nerve-shredding days in the summer of 1939. Strohm himself was obviously not a Jew, but it was the fate of Berlin's Jewish community which had caused him to seek out Russell. Some six weeks earlier he had slid onto an adjoining stool in the Zoo Station buffet and introduced himself, in a quiet compelling voice, as a fellow American, fellow anti-Nazi, and fellow friend of the Jews. He hoped Russell was as interested as he was in finding the answer to one particular question - where were the Jews being taken?

They had gone for a long walk in the Tiergarten, and Russell had been impressed. Strohm exuded a confidence which didn't feel misplaced; he was clearly intelligent, and there was a watchfulness about him, a sense of self-containment more serene than arrogant. Had it ever occurred to Russell, Strohm asked, that those best placed to trace the Jews were the men of the Reichsbahn, those who timetabled, dispatched and drove the trains who carried them away? And if the men of the Reichsbahn provided him with chapter and verse, would Russell be able to put it in print?

Not now, Russell had told him - the authorities would never allow him to file such a story from Berlin. But once America had entered the war, and he and his colleagues had been repatriated, the story could and would be told. And the more details he carried back home the more convincing that story would be.

In a week or so's time, Strohm had informed him, a trainload of Berlin's Jews would be leaving for the East. Did Russell want to see it leave?

He did. But why, Russell had wanted to know, was Strohm taking such a personal interest in the Jews? He expected a standard Party answer, that oppression was oppression, race irrelevant. 'I was in love once,' Strohm told him. 'With a Jewish girl. Storm troopers threw her out of a fourth floor window at Columbiahaus.'

Which seemed reason enough.

Strohm had suggested the simple Ringbahn code, and six days later Russell's phone had rung. Later that night he had watched from a distance as around a thousand elderly Jews were loaded aboard a train of ancient carriages in the yard outside Grunewald Station, not a kilometre away from the house where his ex-wife and son lived. A few days later they had watched a similar scene unfold a few hundred metres south of Anhalter Station. The previous train, Strohm told him, had terminated at Litzmannstadt, the Polish Lodz.

This was the fourth such night. Russell wasn't sure why he kept coming - the process would be identical, like watching the same sad film over and over, almost a form of masochism. But each train was different, he told himself, and when a week or so later Strohm told him where each shipment of Jews had ended up, he wanted to remember their departure, to have it imprinted on his retina. Just knowing they were gone was not enough.

The two men had reached the end of their canyon, and a tall switch tower loomed above them, a blue light burning within. As they climbed the stairs Russell could hear engines turning over somewhere close by, and the clanking of carriages being shunted. Up in the cabin there were two signalmen on duty, one close to retiring age, the other younger with a pronounced limp. Both men shook hands with Strohm, the first with real warmth; both acknowledged Russell with a nod of the head, as if less certain of his right to be there.

It was an excellent vantage point. Across the Ringbahn tracks, beyond another three lines of carriages, the familiar scene presented itself with greater clarity than usual, courtesy of the risen moon. Three canvas-covered furniture trucks were parked in a line, having transported the guards and those few Jews deemed incapable of walking the two kilometres from the synagogue on the corner of Levetzowstrasse and Jagowstrasse. Taking out his telescopic spyglass - a guilty purchase from a Jewish auction two years earlier - Russell found two stretchers lying on the ground beside the front van, each bearing an unmoving, and presumably unwilling, traveller.

The remaining 998 Jews - according to Strohm, the SS had decided that a round thousand was the optimal number for such transports - were crowded in the space beyond the line of carriages, and making, in the circumstances, remarkably little noise. Their mental journey into exile, as Russell knew from friends in the Jewish community, would have begun about a week ago, when notification arrived from the Gestapo of their imminent removal from Berlin. Eigh

t pages of instructions filled in the details: what they could and could not bring, the maximum weight of their single suitcase, what to do with the keys of their confiscated homes. Yesterday evening, or in some cases early this morning, they had been collected by the Gestapo and their Jewish auxiliaries, taken to the synagogue, and searched for any remaining passports, medals, pens or jewellery. Then all had been issued with matching numbers for their suitcases and themselves, the latter worn around the neck.

'The Reichsbahn is charging the SS four pfennigs per passenger per kilometre,' Strohm murmured. 'Children go free.'

Russell couldn't see any children, although his spyglass had picked out a baby carriage lying on its side, as if violently discarded. As usual, the Jews were mostly old, with more women than men. Many of the latter were struggling under the weight of the sewing machines deemed advisable for a new life in the East. Others, worried at the prospects of colder winters, were carrying small heating stoves.

The loading had obviously begin, the crowd inching forward and out of his line of vision. At the rear, a line of Jewish auxiliaries with blue armbands were advancing sheepdog-style, exhaling small clouds of breath into the cold air, as their Gestapo handlers watched and smoked in the comfort of their vehicles.

There were seven carriages in the train, each with around sixty seats for a hundred and fifty people.

One man walked back to one of the auxiliaries and obviously asked him a question. A shake of the head was all the response he got. There was a sudden shout from somewhere further down the train, and it took Russell a moment to find the source - a woman was weeping, a man laid out on the ground, a guard busy slitting open a large white pillow. There was a glint of falling coins, a sudden upward fluttering of feathers, white turning blue in the halo of the yard lamp.

There was no more dissent. Twenty minutes more and the yard was clear, the furniture vans and cars heading back toward the centre of the city, leaving only a line of armed police standing sentry over the stationary, eerily silent train. Feathers still hung in the air, as if reluctant to leave.

A few minutes later a locomotive backed under the bridge and onto the carriages, flickers of human movement silhouetted against the glowing firebox. A swift coupling, and the train was in motion, moonlit smoke pouring up into the starry sky, wheels clattering over the points outside Puttlitz Strasse Station. Even in the spyglass, the passengers' faces seemed pale and featureless, like deep sea fish pressed up against the wall of a moving aquarium.

'Do we know where it's going?' Russell asked, as the last coach passed under the bridge.

'That crew are only booked through to Posen,' Strohm said, 'but they'll find out where the next crew are taking it. It could be Litzmannstadt, could be Riga like the last one. We'll know by the end of the week.'

Russell nodded, but wondered what difference it would make. Not for the first time, he doubted the value of what they were doing. Wherever the trains were going, there was no way of bringing them back.

He and Strohm descended the stairs, retraced their path between the lines of carriages to the distant bridge. After climbing the steps to the street they separated, Russell walking wearily south, his imagination working overtime. What were those thousand Jews thinking as their train worked its way around the Ringbahn, before turning off to the East? What were they expecting? The worst? Some of them certainly were, hence the rising number of suicides. Some would be brimming with wishful thinking, others with hope that things weren't as bad as they feared. And maybe they weren't. Two families that Russell knew had received letters from friends deported to Litzmannstadt, friends who asked for food packages but claimed they were well. They were obviously going hungry, but if that was the worst of it Russell would be pleasantly surprised.

He reached home soon after midnight. Effi was already in bed, the innocence of her sleeping face captured in the grey light that spilt in from the living room. Staring at her, Russell felt tears forming in his eyes. It really was time to leave. But how was he going to get them both out?

Propagandists

Shortly before five the following morning, Effi Koenen let herself out of the apartment and walked down to the stygian street. The limousine was ticking over, its slitted headlights casting a pale wash over a few yards of tarmac. The only evidence of the driver was the bright orange glow of a cigarette hanging in mid air. It seemed absurd that the studio still had petrol to burn when the military was apparently running so short, but Goebbels had obviously convinced himself that his movie stars were as vital to the war effort as Goering's planes or the army's tanks, and on a cold November morning Effi found it hard to disagree with him.

'Good morning, Fraulein Koenen,' the driver said, expunging his cigarette in a shower of sparks. She recognised the voice. Helmut Beckman had first driven her to work almost ten years earlier, and she still felt grateful for the trouble he'd taken to calm her beginner's nerves.

Effi took the seat beside him, as she did with most of the drivers. As she'd once told a disbelieving co-star, she felt a fraud sitting in the back - she was happy to play royalty on stage or on screen, but not on the journey to work. The view and the conversation were also better, although these days the former usually amounted to a black tunnel stretching into an uncertain distance.

'I took my wife to see Homecoming at the weekend,' Beckmann said once they had turned the first corner, heading for the Ku'damm. 'You were very good.'

'Thank you,' Effi said. 'And the film?'

There was a short silence, as the driver arranged his thoughts. 'It was well done,' he said eventually. 'I can see why it won that prize at the Venice Film Festival. The story was...well, there wasn't much of a story, was there? Just a succession of terrible things happening one after the other. It was a bit...I suppose transparent is the word. The writer had his point to make, and everything was lined up so he could. But I guess when you work in the business you notice things like that. And it was certainly better than most. My wife loved it, though she was really upset that you were killed.'

'So was I,' Effi said lightly, although in fact she'd been rather glad. Her character, a German schoolteacher in the territories acquired by Poland in 1918, had succumbed to a stray Polish bullet only minutes before salvation arrived for her fellow Germans in the form of the invading Wehrmacht. She had hoped that her overblown martyrdom would further undermine the credibility, and propaganda value, of the film, but from what she could gather, Frau Beckmann was far more typical than her husband. According to John, acts of violence against Polish POW workers had risen markedly since the film's release a few weeks earlier.

'But she didn't think much of the lawyer,' Beckmann added. 'And when I told her Joachim Gottschalk had turned down the part she got all weepy. She still hasn't got over what happened to him.'

'Few of us have,' Effi admitted. 'Joschi' Gottschalk had committed suicide a couple of weeks earlier. He had been one of Germany's favourite leading men, particularly among female cinema-goers, and the Propaganda Ministry had been more than happy to bank his bulging box office receipts so long as he kept quiet about his Jewish wife and half-Jewish son. But Gottschalk had chosen to parade his wife before a social gathering of high-level Nazis, and Goebbels had blown his diminutive top. The actor had been ordered to get a divorce. When he refused, he was told that the family would be separated by force; his wife and child would be sent to the new concentration camp at Theresienstadt in the Sudetenland, he to the Eastern Front. Arriving at the film star's home to enforce this order, the Gestapo had found three dead bodies. Gottschalk had taken what seemed the only way out.

News of his fate had not been officially released, but as far as Effi could tell, every man, woman and child in Berlin knew what had happened, and many of the women were still in mourning. There had even been talk of a studio strike by his fellow professionals, but nothing had come of it. Effi hadn't particularly liked Gottschalk, but he'd been a wonderful actor, and his family's fate had offered a chilling reminder - if one was really

needed - of the perils of saying no to the Nazi authorities.

'What are you shooting today?' Beckmann asked, interrupting her reverie. They were driving through the Grunewald now, following the red lights of another limousine down the long avenue of barely visible trees. A procession of stars, Effi thought dryly.

'We're re-shooting the interiors with Hans Roeder's replacement,' she said. 'There aren't many, and they decided it was easier to shoot them again with Heinz Hartmann than write the character out of those scenes which haven't been shot.' Hans Roeder had been one of the few Berliners killed in a British air raid that year, and only then by falling shrapnel from anti-aircraft fire. Unlike Gottschalk he had been unpopular, essentially talentless, and a ferocious Nazi. A Goebbels favourite.

How much longer, she asked herself. She had always loved acting, and over the years she'd gotten pretty damn good at it. Over the last ten years she'd done her share of propagandist films and stage shows - one of her and John's favourite pastimes had been ridiculing the stories the writers came up with - but she had also done work that she was proud of, in films and shows which weren't designed to canonize the Fuhrer or demonize the Jews, which did what she thought they were supposed to do, hold up a mirror to humanity, loving if possible, instructive if not.

But now there was only the propaganda, and today she would be back in the costume of a seventeenth-century Prussian countess, bravely resisting a Russian assault on Berlin. The moral of the film was clear enough: the writers had not burdened the story with any conflicting ideals. As far as she could tell, the main crime of the Russians - apart, of course, from their initial insolence in invading Germany - lay in their physiognomy. The casting director had scoured the acting profession for men with a Slavic turn of ugliness, and come up with more than enough to fill the screen.

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave

Diary of a Dead Man on Leave The Dark Clouds Shining

The Dark Clouds Shining Masaryk Station (John Russell)

Masaryk Station (John Russell) Zoo Stationee

Zoo Stationee Zoo Station jr-1

Zoo Station jr-1 Masaryk Station

Masaryk Station One Man's Flag

One Man's Flag Potsdam Station jr-4

Potsdam Station jr-4 Stattin Station jr-3

Stattin Station jr-3 Masaryk Station jr-6

Masaryk Station jr-6 Silesian Station (2008) jr-2

Silesian Station (2008) jr-2 Jack of Spies

Jack of Spies Silesian Station (2008)

Silesian Station (2008) The Moscow Option

The Moscow Option The Red Eagles

The Red Eagles Zoo Station

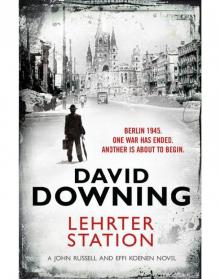

Zoo Station Lehrter Station

Lehrter Station Lehrter Station jr-5

Lehrter Station jr-5